Terry and Keith in Sicily, 2015

Obituary in Gay Times, 30 August 2022

Terry Sanderson: GAY TIMES Magazine’s longest serving columnist and LGBTQ+ rights activist – obituary

We are sad to report that Terry Sanderson, GAY TIMES Magazine’s longest serving columnist, died aged 75 on 12 June 2022.

This appreciation of Terry’s life is written by his partner of 40 years, Keith Porteous Wood. They became civil partners in 2006 after being together for 25 years. As Keith said: “Love at first sight to nursing him to his last, with barely a day not spent together.”

As the HIV/AIDS pandemic was starting to take hold in 1983, GAY TIMES Magazine commissioned Terry to write a monthly feature about the media’s shameless outpourings of hatred of gay people. It was called MediaWatch, which Terry continued to write for 25 years.

Words by Keith Porteous Wood

Terry took his brief very seriously and read every newspaper over that quarter of a century. And that was quite an undertaking when none were online.

All this reading – the principal offenders were The Sun, Mail, Express and News of the World – gave him plenty of material to complain to media regulators, and often also about the media regulators. This running battle went on for decades, but gradually the homophobia largely subsided. As fellow journalist Patrick Strudwick wrote “This Man Spent 25 Years Fighting Newspapers Over Their Anti-Gay Reporting And Finally Won” but there was a bigger prize still. The media’s homophobia had stoked homophobia in the readers and legitimised it. Once the media homophobia largely disappeared, open homophobia reduced and became unacceptable.

Terry’s gay activism started long before MediaWatch. In the South Yorkshire mining village where he was born, he came out in the 1970s while fighting the local council for its refusal to allow a gay disco. He won. Also, to help alleviate gay people’s isolation and lack of positive information he set up a local CHE group and, from his tiny bedroom, a gay mail order business called Essentially Gay.

Photography by Malcolm Trahearn

A curious spin off from MediaWatch was the Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge asking Terry to write a book on coming out. They accepted his script then bottled out of publishing it – he had pulled no punches about the sexual aspects. SPCK offered to get someone else to publish it, but Terry said he had fulfilled his part of the bargain and wanted the agreed writing fee. They relented and the money financed Terry’s new publishing arm, The Otherway Press. The SPCK book reappeared little altered as How to Be a Happy Homosexual, which went through numerous editions and was published in other languages, as were some of the other books he wrote. Readers of those books regularly thanked him for having transformed their lives. Sir Ian McKellen has just written “25 years ago when I was discovering the delights of coming out, Terry’s journalism and books were an eye-opener – always rational and indignant, effortlessly on the high moral ground.”

Shortly before he died, Terry reflected on the dreadful harm the churches had meted out to gay people, but then smiled at the irony of society’s growing acceptance of homosexuality now contributing to the demise of the churches. Back in the 1960s, he had thought homophobia to be unstoppable, while the power of the churches would dissipate. It was his growing realisation that the opposite was more likely that drove him into fighting for secularism.

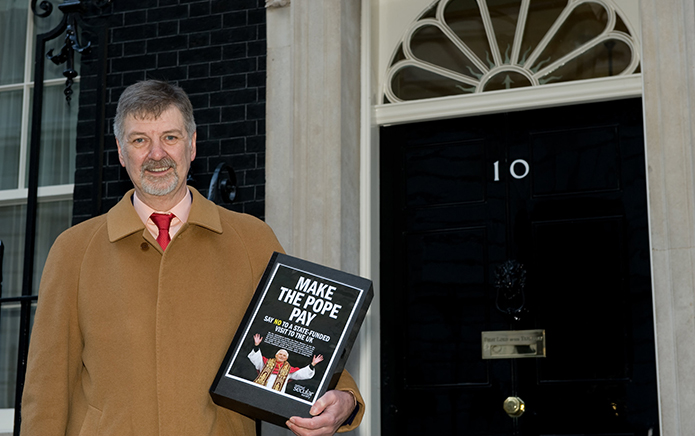

And that was what motivated him to become a secularist and play an active role in the National Secular Society for a quarter of a century, much of it as its president. He was especially proud of having instigated the protest against Pope Benedict’s visit which stretched from Hyde Park Corner to Piccadilly Circus.

One of the last letters Terry received was from veteran gay rights campaigner Peter Tatchell:

“I want you to know how much I admire and appreciate the magnificent contribution you have made over so many decades, from GAY TIMES MediaWatch monthly column for 25 years to How To be a Happy Homosexual, your superb work that transformed the National Secular Society into such an effective and influential organisation – and much more. After you are gone, your legacy will remain.”

Terry signed off his final Facebook post with “Goodbye and try to be kind to each other.” His obituary in The Times was headed “Compassionate gay rights campaigner, secularist and Dietrich devotee.”

One of his last concerns was the rights of gay people and women being seriously eroded in the US, for example with the overturning of the Roe v. Wade case that had allowed abortion in every state. He warned that religious campaigners, some heavily funded by American evangelists, are already intent on doing the same here and in mainland Europe.

He pleaded for the gay community to be vigilant and strive to keep the rights that Terry, Peter Tatchell and many others fought so hard to win.

From The Times, August 06 2022

Terry Sanderson, 75: Compassionate gay rights activist, secularist and Dietrich devotee

It wasn’t until Terry Sanderson’s parents read in a local newspaper of their son’s campaigning for a council function room for single-sex dances that they realised he was gay. It was the late 1970s in Maltby, a mining town in South Yorkshire, and although Terry’s parents were supportive, his sexuality “wasn’t talked about”, he said.

“I hated the contempt and cruelty that was shown to anyone ‘found out’ to be gay and I became determined to do my bit to change things,” he wrote at the start of a courageous lifelong campaign to change the public perception of homosexuality.

One of his first moves in the wake of the decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1967 was to set up in 1974 a mail-order publishing business, Essentially Gay, from his bedroom, importing literature and self-help guides from the US. Although of innocent content, the books were frequently impounded at Customs and Excise. In 1984 books worth £1,600 were seized. It led Terry to close the business down.

A year earlier he had written a piece for Gay Times about the media’s negative coverage of gay people particularly during the height of the HIV/Aids pandemic, and was asked to turn it into a monthly column. Called Mediawatch, he compiled it for 25 years, reading every newspaper every day and steadfastly complaining to — and running fierce battles with — the media regulators.

At the same time Terry was working alongside the agony aunt Claire Rayner on her column in Woman’s Own, and they became friends. When in 1986 he wrote How to be a Happy Homosexual, Rayner wrote the foreword, describing it as “jam-packed with commonsense advice . . . should leave its readers feeling more relaxed about themselves and their lives”.

The book was originally commissioned by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, but Terry ended up publishing it himself under The Other Way Press.

He went on to write other self-help books, including A Stranger in the Family: How to Cope if Your Child is Gay, but Happy Homosexual remained his bestselling title. It was published in other languages and ran to several editions and there was barely a month when he wasn’t thanked by readers for helping to transform their lives.

Terry Sanderson was born in 1946, the youngest of three boys, to Fred, a coal miner for 50 years, and Margaret (née Goodgrove). It was a childhood beset by money worries — Terry recalled the humiliation when one of his shoes fell apart during a school play — but family life was happy.

He left Maltby Secondary Modern at 15 and, tapping into his instinct for helping others, became a social worker. Working with adults with learning difficulties, he started in the 1970s at the Beechcroft unit at Rotherham hospital, moved in the mid-1980s to Friern Hospital, north London, and finally to Ealing, west London. He retired at 57 in 2004.

In 1981 he met Keith Porteous Wood, a finance director and they entered a civil partnership in 2006. Keith was also the executive director of the National Secular Society, and Terry, already a member, became more actively involved in it, founding a weekly newsletter, NSS Newsline.

His experiences in gay activism had convinced him that much opposition to homosexuality was based on religious doctrine and his instinct was to try to limit the ability of religious organisations to impose their beliefs on others. From 2006 to 2017 he was NSS president, and oversaw a shift in the organisation’s focus from atheism to secularism.

In 2008 the NSS played a role in the abolition of the blasphemy laws in England and Wales, and in 2010 Terry helped to organise a 20,000-strong protest against Pope Benedict’s state visit, a march that stretched from Hyde Park Corner to Piccadilly Circus in London.

Away from campaigning, Terry was a devotee of Marlene Dietrich and collected memorabilia. He loved the films of the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s and each year put on a benefit screening at The Cinema Museum in Kennington. Humorous, courageous and considerate to the end, Terry signed off his last entry on Facebook with: “Goodbye — and try to be kind to each other.”

From The Guardian, 19 July 2022

By Keith Porteous Wood

My partner, Terry Sanderson, who has died aged 75, was an early gay rights activist. He was devoted to fighting injustice, and much of his working life was spent helping adults with learning disabilities, initially in Rotherham, South Yorkshire, and then in Ealing, west London, where we later settled.

The youngest son of a miner, Sandy, and his wife, Margaret (nee Goodgrove), a farmworker, Terry was born into grinding poverty in the mining village of Maltby in South Yorkshire, where he went to Maltby secondary modern school, leaving without any qualifications.

In the 1970s, when the local council refused to allow a gay disco that Terry hoped to organise on local authority premises, he challenged the decision in the local paper. By doing so, he came out to both the village and his family, who were supportive of him and, later, of us both.

He went on to form a local branch of the Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE) and from his bedroom also established, in 1974, Essentially Gay, a mail-order company to help those who were closeted and isolated further afield. It ran until 1984.

We met in 1981 during a CHE social weekend. Our binding passion was gay rights, and seeking to combat what we saw as the biggest obstacle to emancipation: religious privilege and harmful doctrine – hence our commitment to secularism.

Terry’s greatest talents lay in his journalism and writing. The portfolio of gay self-help books he wrote transformed the lives of many. Most popular was How to Be a Happy Homosexual (1986), which went through numerous editions and translations.

Apart from three years in the early 80s working as an agony aunt for Claire Rayner at Women’s Own, from 1970 to 2004 Terry worked as a disability support worker or similar, refusing numerous offers of promotion due to his determination to stay close to the service users. He worked at Beechcroft (attached to Rotherham hospital) for more than 10 years, then, when he moved to London to live with me, at Friern (mental) hospital for two years. Finally, he worked at Cowgate day centre, run by Ealing council, for more than a decade, before retiring at the age of 57 in 2004.

From 1983 to 2007, Terry read every newspaper in order to compile the monthly Mediawatch column for Gay Times, highlighting media homophobia. He complained frequently to the media regulators, contributing in no small part to the much more tolerant attitude that we now witness.

Terry and I worked together at the National Secular Society from 1996 to 2020. He helped build membership through the popular weekly Newsline, which he founded, as well as volunteering for the society. Eleven of his 20-plus years with the NSS were as president.

Unassuming yet popular, Terry was a compassionate fighter for justice. His last post on Facebook, announcing his imminent demise from cancer, concluded: “Be kind to each other.”

Terry is survived by me and by his brother Albert.

URL: Terry Sanderson obituary | LGBTQ+ rights | The Guardian

From Rotherham Advertiser: ‘Tributes paid to gay rights campaigner Terry Sanderson‘

By Michael Upton | 26/06/2022

A TIRELESS campaigner for gay rights and disability support drew tributes from famous names after his death at the age of 75.

Maltby-born writer and journalist Terry Sanderson died peacefully at the home in London he shared with partner Keith Porteous on June 12 after suffering from cancer.

He had signed off his last Facebook post: “Goodbye a and try to be kind to each other.”

Human rights activist and Stonewall founder Peter Tatchell said Terry had enjoyed an “extraordinary life” and been an inspiring LGBT+ advocate, while actor Ian McKellen tweeted: “Thirty-four years ago, when I was discovering the delights of coming out, Terry Sanderson’s journalism and books were an eye-opener always rational and indignant and good-humoured, effortlessly on the higher moral ground.”

Terry set up a mail order book service called Essentially Gay from his home in Maltby after homosexuality was decriminalised offering those who were isolated and unable to obtain information and support.

He imported books from the US, which were frequently impounded by homophobic customs officials on both sides of the Atlantic.

Keith said: “His talents as an incisive and provocative writer and journalist were put to so many uses in the service of gay rights and secularism.

“Some of his books are shown here but over the decades he wrote many more, especially gay self-help books, which ran into numerous editions.

“Hardly a month went by without readers of these books thanking him movingly for having transformed their lives.”

Terry also played a leading role for nearly 25 years in developing the National Secular Society, and was its president for 11 years.

For more than 20 years, he wrote the monthly Mediawatch columns in Gay Times, which were later published as a book.

Keith added: “There was another, delightful, side of Terry; he was popular, well-liked, and had a wide circle of friends.

“And he was humble; he never sought out praise or recognition.

“He loved music and was a devotee of Marlene Dietrich and had a wicked sense of humour.

“He wrote humorous books and even plays, and he was always searching for outstanding historic cinema clips \_ the best of each year’s crop were screened every Christmas in a popular benefit show for the Cinema Museum.”

Keith said Terry had borne his illness “with characteristic fortitude and dignity”.

He added: “His loving family were entirely supportive of him as a gay man and, later, of us as partners.

“His rich and varied life was devoted to serving others and fighting injustice. “Almost his entire working life was spent helping adults with learning difficulties, or campaigning for gay rights and secularism, our dual passions.”

Terry (pictured) declared at the end of April on Facebook that he was placing himself “in the hands of the angels, i.e. the Macmillan nurses” and Keith praised Macmillan Cancer Support, Marie Curie and paramedics for their “selfless care of the highest order”, as well as Meadow House Hospice in Ealing, west London.

He added: “Disclosing his terminal illness provoked a flood of touching tributes.

“Most people do not live to hear their eulogies, but he and I have drawn great comfort from them.”

URL: Tributes paid to gay rights campaigner Terry Sanderson (rotherhamadvertiser.co.uk)

From the National Secular Society: ‘NSS mourns the loss of Terry Sanderson’

Posted: Mon, 13 Jun 2022

The National Secular Society is saddened to report the death of our former president Terry Sanderson aged 75.

Over the last few years, Terry had undergone various cancer treatments. His cancer returned earlier this year and attempts to treat the condition were unsuccessful. He leaves behind his partner of 40 years, current NSS president Keith Porteous Wood.

Childhood

Terry Sanderson was born in Maltby, South Yorkshire, in 1946. The son of a coal miner, he grew up in poverty. He was the youngest of three brothers. In his autobiography he describes his family as “loving” and his childhood as “happy and sheltered”.

Gay activism

Terry realised as a teenager that he was gay but found it difficult to meet other gay men until he joined the Campaign for Homosexual Equality. He became involved in gay activism when the local council refused hire of their function rooms for a gay disco and ended up coming out in a local newspaper interview. This was a shock to his family, but they were supportive.

As a young man, Terry tried a ranged of jobs, most notably working as a psychiatric nurse and occupational therapist. However, he had a passion for writing, and he wrote regularly for Gay News. He later got a job as part of the Women’s Own agony aunt team. His talent for helping others and providing advice led him to write How to be a Happy Homosexual, the book he wished he had had when he was young. This was followed by other books providing advice to gay men and their families.

As gay activist, Terry was at the forefront of the social and legal battles that radically transformed the lives of gay people in Britain. This included the infamous Gay News trial, where the newspaper was convicted of blasphemous libel following the publication of an erotic poem about Jesus Christ. This was the last time the blasphemy laws would be applied in England and Wales.

NSS Presidency

Terry’s experiences in gay activism had shown him that much opposition to homosexuality was based on religious doctrine. He realised the need to limit the ability of religious organisations to impose their beliefs on others. He joined the NSS and became more actively involved when his partner Keith became Executive Director in 1996. Terry joined the NSS Council and was President from 2006-2017.

During his time as President, Terry oversaw a shift in the organisation’s focus from atheism to secularism. He summarised his position thus:

“I would like us to position ourselves as a purely secularist organisation with a focused objective, that will not only champion human rights above religious demands but will also accept that religion has a place in society for those who want it, but on terms of equality, not privilege.”

Notable campaigns during this period were the abolition of the blasphemy laws, which was finally achieved in England and Wales in 2008, and the protest against Pope Benedict’s state visit to the UK in 2010.

Terry was succeeded as president by his civil partner, Keith Porteous Wood, who had just retired as Executive Director. He remained on the NSS council when his health permitted, finally standing down in 2020.

Cancer treatments

Terry was diagnosed with bladder cancer in 2017. He was open about his condition and wrote about his treatment in detail. He disliked the cliché that cancer is something that a patient must “battle” or struggle against, and his description of treatment suggests that it was something to be endured while experts did battle on his behalf.

Although Terry’s treatments were initially successful, his cancer returned. In 2022, he announced that his recent immunotherapy treatments had been unsuccessful and that he was receiving palliative care.

He died at home on Sunday 12th June.

NSS comment

Stephen Evans, chief executive of the National Secular Society, commented:

“Terry’s positive vision and leadership were instrumental in revitalising the NSS and turning it into the effective campaigning organisation it is today.

“His advocacy of secularism was driven by a keen sense of fairness and justice – and a healthy disdain for religious leaders moralising about how others should live their lives. Terry’s gay rights activism touched the lives of so many people – empowering them to be themselves and speak out against the injustice and bigotry they faced.

“I will remember him fondly for his good humour and no-nonsense approach to campaigning. His absence will be felt for many years to come.”

Former NSS president Denis Cobell also sent the following message of condolence:

“I am saddened to learn of Terry’s death. He was my successor in 2006 as President of the NSS for the next eleven years. When I was President, Terry was a Vice-President alongside Jim Herrick. During that time Terry did much to assist in preparing the Annual Report. He was also the author and collator of the NSS weekly Newsline. At the time of the 150th anniversary of the NSS founding in 1866 by Charles Bradlaugh, Terry wrote in the celebratory brochure in 2016: ‘Bradlaugh’s attacks on religion, particularly on the outrageous privileges of the Established Church, were brilliant, scorching and necessary’. Unfortunately, many of those privileges still exist despite the Church’s decline. It was good to see Terry last October at the unveiling of a new bust on Bradlaugh’s grave in Brookwood Cemetery, Woking. He was smiling and happy – how we should remember him. Terry had charm and a positive approach to life. He will be sorely missed, and I offer my condolences.”

URL: NSS mourns the loss of Terry Sanderson – National Secular Society (secularism.org.uk)

From Keith Porteous Wood, President of the National Secular Society: ‘Former NSS president Terry Sanderson’

Posted: Mon, 13 Jun 2022 by Keith Porteous Wood

An obituary to Terry Sanderson, who died on June 12th 2022, by his civil partner Keith Porteous Wood.

Terry in 1978, from a drawing by Lysbeth M Wilson.

I regret to inform you of Terry’s death, at the age of 75. He died peacefully and, as he wished, at the home we have shared so happily for forty years. He bore his illness with characteristic fortitude and dignity.

Terry was born in Maltby, a poor working class mining village in South Yorkshire. His loving family were entirely supportive of him as a gay man (which they first discovered from the local newspaper), and – later – of us as partners.

His rich and varied life was devoted to serving others and fighting injustice. Almost his entire working life was spent helping adults with learning difficulties, or campaigning for gay rights and secularism, our dual passions.

Not long after homosexuality was decriminalised, he bravely set up a mail order book business, called Essentially Gay, from his tiny bedroom in the very macho Maltby to help those who were isolated and unable to obtain information and support. He even imported books from the US, which despite being entirely innocent, were frequently impounded by cruelly homophobic custom officials on both sides of the Atlantic.

His talents as an incisive and provocative writer and journalist were put to so many uses in the service of gay rights and secularism. Some of his books are shown here but over the decades he wrote many more, especially gay self-help books, which ran into numerous editions. Hardly a month went by without readers of these books thanking him movingly for having transformed their lives.

He made his monthly Mediawatch columns in Gay Times, a campaigning platform to challenge the inhumane treatment of gay people in the media, which he continued uninterrupted for a quarter of a century – necessitating him reading every newspaper. This was reinforced by his frequent complaints to, and fierce battles with, media regulators. It all helped to create the hugely more compassionate coverage we enjoy in this country today. These hundreds of columns have become social history and are also the subject of a book. They are being curated by the Queer Britain museum and are searchable here.

Terry played a leading role for nearly 25 years in developing the National Secular Society, and was its president for 11 years. His skills as a journalist and writer were put to good use compiling articles, news releases and the popular weekly NSS Newsline, which he founded.

But there was another, delightful, side of Terry; he was popular, well-liked, and had a wide circle of friends. And he was humble; he never sought out praise or recognition.

He loved music and was a devotee of Marlene Dietrich and had a wicked sense of humour. He wrote humorous books and even plays. He was always searching for outstanding historic cinema clips. The best of each year’s crop were screened every Christmas in a popular benefit show for the Cinema Museum.

Terry declared at the end of April on Facebook that he was placing himself “in the hands of the angels, i.e. the Macmillan nurses.” Macmillan Cancer Support, Marie Curie and paramedics have indeed provided selfless care of the highest order, as have the palliative care specialist nurses associated with the Meadow House Hospice (which also provides care in the community) in Ealing, west London. We cannot thank them enough. We are similarly grateful for the wonderful care and world-class treatment Terry received at the Charing Cross Hospital, Hammersmith, west London.

Terry updated his autobiography to include references to his experience with cancer. Disclosing his terminal illness provoked a flood of touching tributes. Most people do not live to hear their eulogies; but he (and I) have drawn great comfort from them. Two are shown below:

From Human Rights activist Peter Tatchell:

I am so sad to hear about your diagnosis. My thoughts are with you at this difficult time.

I want you to know how much I admire and appreciate the magnificent contribution you have made over so many decades, from Gay Times Media Watch monthly column for 25 years to How To be A Happy Homosexual, your superb work that transformed the National Secular Society into such an effective and influential organisation – and much more.

After you are gone, your legacy will remain.

We are much indebted to you – and Keith.

Your personal and human rights partnership of nearly five decades has been inspirational.

I am so proud to have known you both and your amazing efforts for LGBT+ and other human rights.

You will be remembered always with love and affection.

From Sir Ian McKellen:

25 years ago when I was discovering the delights of coming out, Terry’s journalism and books were an eye-opener – always rational and indignant, effortlessly on the high moral ground. I hope he is proud of his influence on the legal and social changes which his reporting encouraged.

All the best and more, as the days go by.

___

Thank you to everyone else who sent us tributes for your kind words.

As Terry concluded his final Facebook post:

“Goodbye – and try to be kind to each other.”

Terence Arthur Sanderson, 17 November 1946, Maltby, S. Yorkshire

You may wish to contribute in Terry’s memory to Cancer Research, Macmillan Cancer Support, Marie Curie, LNWH Charity – Meadow House Hospice and/or Charing Cross Hospital.

URL” Terry Sanderson – National Secular Society (secularism.org.uk)

Email from Lord Black of Brentwood to Keith Porteous Wood, Terry’s partner, in 2023.

I remember well Terry’s Mediawatch column for GT and looked at it regularly when I was at the Press Complaints Commission. It helped change attitudes.

We have indeed made good progress – always more to do both here, and internationally – and much of that is down to the work of you, Terry and other fearless campaigners. All those who hold this issue dear are indebted to you.

Patrick Strudwick Interview 15 June 2019

Terry Sanderson charted media slurs against LGBT people from the 1980s onwards. He told BuzzFeed News how he won the first-ever ruling against the press for its anti-gay coverage.

by Patrick Strudwick BuzzFeed UK LGBT Editor

Poofters. Benders. Shirtlifters. Bumboys. Lezzies. This was how British tabloid headlines referred to gay men and lesbians in the 1980s — an echo of the taunts heard on the street before a beating. The stories beneath would expand on the pejoratives, justifying them with news of “sick”, “evil”, “predatory” gays — all arising from a presumption: that readers would agree.

It came at the worst time. After the burgeoning liberation movement and the shirts-off, arms-up disco era, gay men started dying in the hundreds, then thousands.

As AIDS hit in the early 1980s, Fleet Street, then the home of Britain’s newspaper industry, responded by blaming gay people for their own deaths; lying about the causes of the disease; calling for a return to the closet, to abstinence, and even to prison. Later, when the Conservative government gagged teachers from discussing homosexuality, many newspapers roared in approval.

But there was one gay man who decided to fight back, with words of his own.

From 1983, Terry Sanderson began to document newspapers’ slurs against the community in a column for Gay Times magazine (then the most important gay publication) called “Media Watch”. He dissected the worst — the myths, the stereotyping, the outing of members of the public — and responded to the onslaught with wit and fury, all while providing LGBT people with something invaluable: a voice.

He accused tabloids of turning its coverage of gay people into a “blood sport” — the difference being that “with gay-baiting nobody seems concerned about the barbaric cruelty of it all.” He mocked the most what-the-fuck ludicrous coverage — the Daily Star’s assertion that “the Rottweiler is the gay community’s favourite pet” or the Sun’s headline: “Gays Axe Christmas”. And he lambasted his own community, too — if deemed to betray the cause.

On one occasion, Kenneth Williams, the famously self-hating gay actor, told an interviewer, “Anybody who pretends that two men can live together happily like man and wife is talking a load of rubbish.” Sanderson responded in “Media Watch”: “At the beginning of the interview, Mr Williams proclaims, ‘I am a cult’, although I’m not sure he’s spelt it right.”

The column was only supposed to be a one-off. But he didn’t stop for 25 years, outlasting all the columnists who were frothing when he first started.

He also secured a first: a historic win, holding a newspaper to account for its smears against gay people.

Earlier this year, while on a break from cancer treatment, Sanderson decided to unearth all of his old columns and publish the lot online. The resulting website, GTMediaWatch.org, now provides a unique insight into the period and comprehensive evidence of what the media, politicians, and public figures did during the most pivotal fights in LGBT history: the AIDS crisis, Section 28, the age of consent, civil partnerships, fostering, and adoption.

It’s all there, much of it in newspapers that are not the most obvious culprits.

But the timing bites. As many British papers shift, now encircling transgender people with repurposed taunts, Sanderson’s decades-old polemics about the media’s treatment of “dykes” and “buggers”, and how they pose a threat to children/decency/society, foreshadowed it all.

His column also serves as a warning. This, it says, is where words lead. LGBT people are still bloodied on the street, still defiled by reporters, and now pursued on social media. Fractured, furious Britain poses fresh threats to the marginalised. Sanderson’s words call out to editors: You have a choice.

BuzzFeed News visited him at his home in Ealing, west London, to discover why he stood up to Fleet Street for so long — and what it did to him.

Nothing, it transpires, is what you might expect.

Terry Sanderson lives with his husband, Keith, in the comfy, velvety home they have shared for 35 years. Today Keith pokes his head into the living room to offer tea and hot- cross buns. On his return a few minutes later, Sanderson takes two bites and begins to talk.

He was born in 1946 in Maltby, a Yorkshire mining town, and bred among the community of pit workers, the very people who, as he was later writing his column, would give Margaret Thatcher the middle finger. “Nobody messed with them,” he says.

Sanderson’s voice is soft and rich, his accent rippled with South Yorkshire inflections. Despite the militancy of his writing and the gentility of his manner, there is something of the corduroy about him: sturdy, comfortable, sensible.

“It was always obvious I was gay,” he says of his childhood among the miners. “There was no escaping it — camp as arseholes from day one. But it wasn’t talked about.”

As adolescence became adulthood, isolation engulfed Sanderson. Where, he wondered, were the people like him? It was the 1970s, and the Gay Liberation Front marching through London was far from permeating small-town Yorkshire.

Sanderson decided to do something about it. While working in a photographer’s shop in Rotherham, he founded a local, Yorkshire-based branch of the Campaign for Homosexual Equality, one of the early and rather polite gay groups. The phone started to ring. “I realised there are an awful lot of people isolated and alone and frightened,” he says. But there was an even more basic revelation that would awaken Sanderson. “There were gay people all over the place!’” he exclaims. “Over Maltby, all over Rotherham, everywhere!”

From this, his consciousness grew, fuelling everything that was to come. “I started to read Gay News,” he says, referring to the publication that would become Gay Times, “and see [from its reporting] all these discriminations happening: gay people getting kicked out of their jobs, parents rejecting them.”

His group became more political, dividing its members. Many lived with so much fear as to wish only to remain invisible. “Don’t draw attention” was their attitude, he says.

But instead of this deterring him, it flicked a switch. “I started to think, We want our place; why shouldn’t we have it? It made me look again at the way we were being treated in the press and think, No. You’re wrong. Stop it.”

By now, 1983, he was living in London with Keith and dabbling in journalism, just as the newspapers’ attacks mounted. “I was beginning to see all this stuff and thinking, Where is all this coming from? And, more to the point, where is it going?” It was the year that the AIDS virus was isolated.

Sanderson wrote a piece for the magazine about the media’s coverage of gay people, and impressed, the editor asked him to turn it into a monthly column. He had no idea that for the next quarter of a century it would fall to him to document the anti-gay distortions written by those whose job it was to reveal the truth.

To read any of the early columns is to be jolted by the sheer volume of attacks. In a typical example from 1985, Sanderson is left returning fire on one anti-gay piece after the other, all drawn from a single month. The first, a Sunday People spread under the headline “Ban the Panto Fairies”, saw the comedian Bernard Manning arguing that gay actors should not be allowed on “television, on stage, in clubs or pubs” in order that they don’t “corrupt the children”.

“This is rich,” wrote Sanderson, “coming from someone who for years has made a living out of uttering the most filthy racist abuse imaginable.”

Next was a Spectator columnist who had written that “extreme promiscuity has led to the Aids epidemic… a disease caught by men who bugger and are buggered by dozens or even hundreds of other men every year.”

Much as others might be tempted to suggest a note of envy in the prose, such words, wrote Sanderson, didn’t even warrant their own takedown for one simple reason: They were copied. “Almost word-for-word from a column in the New York Post”.

So Sanderson jibed: “Not able to write his own bigoted column he plagiarises other people’s.”

It wasn’t just the national newspapers. In the same column, Sanderson selected a delightful mezze of local paper bigotry. “Gays are EVIL” was the headline in a recent edition of the Bromley Leader. The Plymouth Evening Herald described a mere advert for a gay club as “an offensive gay club poster”. Meanwhile, the Solihull Daily Times blared in a headline: “Row over poofs and queers”.

In the same column, he reported that the Sun, Britain’s bestselling newspaper, had “negative gay stories almost every day for the past few weeks”. In one, the paper branded a council leader “barmy” for campaigning for black and gay people to be protected from murder. “Does Mr Murdoch’s excuse-for-a-newspaper applaud mindless thuggery then?” Sanderson asked. “It seems so.”

His column warned that “these are crude and extreme attacks but they are becoming more frequent,” with a call to arms that would be repeated often in the forthcoming years. “It’s up to us all to ensure we don’t let these slanders go unchallenged,” he wrote, encouraging readers to complain to the editors as it takes “a long time to counter hatred and persecution once it takes hold.”

These attacks, in the press and in the street, came at a time when there were no legal protections for LGBT people: the law did not recognise anti-gay hate crimes, you could be fired or evicted because of your sexuality, and the age of consent was 21 for gay men.

But it was the AIDS crisis, rising through the 1980s, that brought Sanderson’s column into terrifying focus.

Shortly after the Sun’s near-daily anti-gay coverage, The Times declared its official position in a leader editorial: “Many members of the public are tempted to see in AIDS some sort of retribution for a questionable style of life.”

“It’s all our fault, is it?” fumed Sanderson in “Media Watch” before quoting a headline in the same edition of the paper: “Is it wise to share a lavatory with a homosexual?”

But the Times, in its tenor, was among friends. “The News of the World carried ‘gay plague’ headlines in three consecutive issues,” wrote Sanderson, detailing each one: “Victims of gay plague long to die”; “My doomed son’s gay plague agony”; “Art genius destroyed by gay killer bug”.

All of which, he wrote, reeked of a “sick self-congratulation” redolent of a self-soothing lie: “It can’t happen to us because we’re straight.”

When the Sun then called gay men “walking time bombs” with the “killer disease AIDS” who are a “menace to all society”, Sanderson wrote to the editor, Kelvin MacKenzie, asking “whether he was prepared to take responsibility for acts of violence which might be incited against gay men by this highly provocative editorial”. This wasn’t hypothetical: people living with AIDS were having petrol bombs thrown through their letterboxes.

MacKenzie’s reply was reported in Media Watch: “I do not accept that our editorial did any more than urge all homosexuals, in the interests of the entire community, to think twice before giving blood.” This did little to dissuade Sanderson from referring to the staff at the tabloid as “Suns-of-bitches”.

Even when the evidence was clear that heterosexuals also had HIV, the Sun, wrote Sanderson, “still insisted that AIDS sufferers were ‘gay plague victims’” and merrily printed headlines unencumbered by facts: “Beer mugs may spread the disease”.

Broadsheet newspapers did not escape the glare of “Media Watch”, either. The Telegraph published a column arguing that it wasn’t scapegoating to accuse gay men of spreading AIDS because “male homosexuals are undoubtedly responsible”.

5/10

Under this quote, Sanderson wrote a multipoint plan of action for any reader wanting to fight the bombardment. He suggested blitzing editors with letters and phone calls to insist on responsible reporting; writing to MPs and the National Union of Journalists; telling friends and family the truth about the virus — anything to counter the lies.

Seeping out of every sentence was not so much Sanderson’s fury as his terror: Friends were dying, gay men were being attacked, but newspapers kept going.

“It became very intense,” he says now, looking away. “The opposition and hostility was day in, day out. ‘Severe’ is not the word. It was horrendously hostile. I thought if this goes on much longer, there’s going to be some kind of terrible reaction.”

Two years later, in 1987, “Media Watch” revealed how much the tabloids had changed. “Perverts Are to Blame for the Killer Plague” was the Sun’s headline on Dec. 12, under which the accompanying leader article asked: “Why do homosexuals continue to share each other’s beds? … Their defiling the act of love is not only unnatural but in today’s Aids-hit world it is LETHAL.”

This was mild compared with the Daily Express, which quoted — without comment — one of its readers: “The homosexuals who have brought this plague upon us should be locked up … Burning is too good for them. Bury them in a pit and pour on quick lime.”

Sanderson feared that homosexuality itself would be recriminalised — not a stretch when the Sun had suggested locking gay people up, since they were, apparently, an “evil threat to society”. And so, Sanderson wrote that, with 4 million readers and other papers emulating its vitriol in a fight for circulation, “The Sun is a serious threat not only to the quality of our lives but now to our very existence.”

He remembers how frightening it was, this malignant wallpaper plastering the country — in part because newspapers were much more powerful and widely read than today. “They were so insistent: Everything about gay life was negative,” he says. At times even other mainstream news outlets cried out. The Guardian warned in 1987 that such coverage represented a “sustained attempt to resurrect the mob”.

Many gay people Sanderson knew at the time simply refused to look at newspapers, “pretending they didn’t exist”. But all the while, he says, much of Fleet Street was “inciting other people to violence” against lesbians and gay men. He feared worsening bloodshed. In a six-month period between late 1989 and early 1990, there were four anti-gay murders just in West London where he lived. It took until 2006 for the first person to be found guilty of such a crime.

“I used to make the point to journalists all the time — words can lead to actions, and the violence of your words can provoke people into feeling justified in actually violating real people in the street,” he says. “They never accepted that was the case.”

In 1988, when Section 28, the new law preventing mention of homosexuality in schools, was in the news, Sanderson again used “Media Watch” to galvanise the community: “Now we must be ready to fight it every step of the way.” The legislation had been born of a media-lit moral panic over books informing children that some people have two mothers.

Once alight, the editorialising became ever more puerile. When activists, for example, “threatened” members of the House of Lords over the bill, the Sun responded: “It could have been worse for their Lordships. The poofters could have threatened to KISS them instead.” (Anti-gay language was often helpfully capitalised.) The People wrote of the same alleged threats: “Time was when we thought hell had no fury like a woman scorned. That’s nothing compared to a poofter peeved.”

Even the insults were inexpertly delivered.

In many of the columns, Sanderson’s tone was so confrontational as to feel as if it could have been written last week; not because of today’s omnipresent fury but because his fuck-you stance was so distinct from the self-loathing that rendered many apologetically congenial at the time.

“I got into that mindset quite deliberately,” he says. “I thought, ‘No, I’m not going to apologise, I’m going to tell ’em. I had to — on behalf of other people who were still frightened and cowed by this aggression from the tabloids. I had to say, ‘No, you can stand up and say fuck off.”

At other points, however, he simply sounded arch, as if sighing while inspecting his nails. When the Evening Standard wailed about a “Storm over gay sex books for 2 year olds” (also during the Section 28 furore), Sanderson countered, “Presumably these books are available in a school for infant prodigies who can read at the age of two?”

And when EastEnders became, in 1989, the first British soap opera to show a gay kiss, Sanderson quoted the Sun: “The homosexual love scene between yuppie poofs was screened in the early evening when millions of children were watching” before puncturing the hypocrisy therein: “just in case any Sun-reading kiddie missed it, the shocking peck was photographically reproduced for their edification”.

The Guardian, which later claimed to be “the world’s leading liberal voice”, was not without fault, either, Sanderson says. He accuses the outlet of “giving a voice to people who should never have one in a paper like that, simply because they felt they should have balance.” Sometimes it was worse than that. “Media Watch” highlighted the reporting of a vicar who had been caught cottaging, entrapped in a public toilet by a policeman, but rather than criticise the police, the Guardian published the defendant’s home address. At one point, its coverage led to gay protesters occupying the newspaper’s offices.

(Much later, in 2004 and 2013, further protests would be staged there, but over anti-trans columns. These contained phrases such as “man in a dress”, “dicks in chicks’ clothing”, “shemales”, “trannies,” and a warning to trans people: “You really won’t like us when we’re angry.”)

Sanderson’s column also mocked newspapers for what they didn’t say. In 1987, When James Baldwin, one of the most important voices of the 20th century, died, “Media Watch” scoffed: “The two subjects on which James Baldwin wrote most passionately were racism and homosexuality. His obituary in The Independent managed to fill three long columns without once mentioning the writer’s gayness.” This omission was an “affront to his memory and to the dignity of the whole gay community”.

Similarly, in 1984, when Gay’s the Word bookshop was raided by Customs and Excise officers, with 144 titles confiscated on the grounds of obscenity — books by such apparent pornographers as Jean-Paul Sartre and Gore Vidal — the column fumed: “No mention in the national newspapers”.

In this, “Media Watch” captured a cold truth: Newspapers were uninterested in the harm committed against gay people because they were too busy committing it themselves.

On occasion, however, the papers would report hate crimes — in order to cheer. When homophobes vandalised a flowerbed that had been planted in Manchester to celebrate Pride, the Sun’s “predictably jeering reaction”, wrote Sanderson, was: “Anti-gay gang wipe out pansies!”

But he didn’t only use his column to fight back. He took action. He went to the Press Council — or “invertebrate Press Council,” as he called them — the body that was supposed to regulate newspapers, and made complaint after complaint after complaint. All of which were, for years, rejected on the grounds of press freedom (“We must be free to call them benders!” was the argument).

But then, in late 1989, a new, liberal man took charge of the council: Sir Louis Blom- Cooper.

“I went to see him,” says Sanderson before lowering his voice conspiratorially. “He said, ‘keep making complaints and it [a successful ruling] might happen.’”

So in early 1990, Sanderson rounded up some recent columns by Gary Bushell, a columnist for the Sun notorious for his anti-gay abuse, and made a complaint to the council. These columns contained such refined terminology as “woofter” and “poof”, attacks on television programmes that “promote homosexuality,” and lines such as, “It must be true what they say about nobody being all bad … even Stalin banned poofs!”

Months later, and for the first time in its history, the Press Council upheld a complaint against a newspaper for using anti-gay language. Sanderson had won.

In its ruling, the council said: “The words ‘poof’ and ‘poofter’… were so offensive to male homosexuals as not to be a matter of taste or opinion” and therefore should only be printed where “necessary for the purpose of proper understanding of the item in which the offensive words appear”.

Sanderson remembers the day the adjudication arrived in the post.

“I jumped in the air,” he says, beaming.

The joy did not last. Along with newspapers bristling with indignity for being told off, the Sun itself responded with the headline: “You Can’t Call ’em Poofers” under which the paper raged against the council for its “lordly manner over language” while accusing gay people of “appropriating” the word “gay” from its dictionary definition.

But the backlash eventually ebbed, says Sanderson, as newspapers began to realise “which way the wind was blowing”. Their readers were changing before they were.

Sanderson’s complaints were not only about journalists’ offensive language, it was also their actions. “Every week in the News of the World there’d be some vicar or actor or someone just getting on with their life and they’d be outed,” says Sanderson. Some of whom had been caught cottaging, thereby revealing how co-joined the anti-gay forces were: “It was the police who told the press.”

One of the most prominent figures to be outed by the press was the chat show host Russell Harty. “He never really recovered,” says Sanderson. But there were also members of the public; in one instance a surgeon was exposed for his HIV status. “He was hounded out of his job because of what the papers were saying, frightening people. I just thought, Why don’t they say that if you follow the correct procedures, nobody is at risk?”

Some public figures fought back, playing the papers at their own game. When the News of the World was tipped off about the sexuality of Gorden Kaye, the beloved ‘Allo ‘Allo actor “went to the Mirror [its rival],” who were “much more sympathetic” and who then published it on Saturday, ruining the Sunday paper’s exclusive.

The outings continued. “It never occurred to them that they were harming people,” he says.

But what about Sanderson? What effect did reading and responding to all this, week in, week out, for decades have on him?

He looks straight ahead. “I was outraged and angry about all of it, but I didn’t let it penetrate,” he says flatly, in almost mechanical defiance, before explaining what distinguished him from many during this period who were simply trying to cope — childhood rejection bleeding, often literally, into adult brutality.

“As a child, I always felt safe in the bosom of my family,” he says, a rarity for LGBT people then, if not now. His relationship built upon this. “If it hadn’t been for Keith, it might have really got to me. He’s always looked after me and made sure no catastrophe overtook me.” Sanderson pauses for a moment. “Although he couldn’t protect me from cancer.”

From the late 1990s, they both worked for the National Secular Society, Sanderson as its president before Keith (whose surname is Porteous-Wood) took over the same role in 2017. Sanderson eked out his modest fee for the column through other journalism and by working as a psychiatric nurse.

And then, a few years ago, the call came: A new editor had decided to ax the column. Sanderson is sanguine about this. “I knew it would have to come one day,” he says. “The magazine was losing money; they had to regenerate it, make it more lifestyle-y.”

Now retired, and no longer scanning the papers every day, he remains aware of what is happening in the media, and it worries him: the new campaign, this time against trans people.

“The whole thing is starting again,” he says. “They seem to need a scapegoat, someone to project all societal discomfort onto. People are fed up with the political system and somebody’s got to pay. It’s usually a minority that can’t hit back.”

IPSO, one of today’s press regulators, is currently conducting a review of newspaper reporting on trans issues. The Times is meanwhile fighting an employment tribunal against a former editor suing for anti-trans bullying and discrimination who argues that the paper’s coverage is itself evidence of this. Many trans people are frightened by the coverage — unable to look, some unable to leave the house. Christine Burns, one of the pioneers of the community who helped create the Gender Recognition Act, told staff at the Guardian last week of the effect anti-trans reporting was having: “I’m scared to death.”

One of the problems regarding how journalists approach the trans community, says Sanderson, is “people don’t understand it, and that was a very similar thing with the early days of gay visibility. It was new to them, and something they thought only existed in a tiny, tiny minority living somewhere not here.”

Sanderson seems, at 73, disconnected at times from the horrors he documented — perhaps necessarily so — but at others, certain memories shake him: the fear-mongering during the AIDS crisis in particular. “Somebody should have been punished,” he says, “for the way they misinformed people to create panic.” As for Kelvin MacKenzie, the then- editor of the Sun? “I’ll never forgive him,” he says.

We change the subject to his recent treatment for cancer. What’s the prognosis now? “Hopefully gone,” he says in a touch-wood voice. “But I’ve got to see [the doctor] again next month for my three-monthly checkup.” As he continues talking about the illness, unspoken parallels begin to resonate, crackling between the malignancy in the body and the stoked malevolence outside.

“It’s always in the back of your mind,” he says, his voice dropping to a hush. “It’s always a possibility that it’s lurking somewhere. Waiting.”

BuzzFeed News approached the Sun for comment. The newspaper declined.

Obituary in The Delius Journal Spring 2023

TERRY SANDERSON (1946-2022) Jim Beavis writes:

In the January Newsletter we reported the death last June of Society member Terry Sanderson, aged 75. His life story is an unusual one. His partner for 40 years, Keith Porteous Wood, who has written his own tribute (see below), kindly directed me to a number of sources for this obituary.

Terence Arthur Sanderson was born in South Yorkshire in 1946, in a poor mining village called Maltby. It wasn’t the easiest place for a teenager to live once he realised hewas gay. He left school at 15 without any qualifications but found his niche in jobs that involved helping people, which included spells as a psychiatric nurse and an occupational therapist. Finding like-minded friends was difficult until he signed up with the Campaign for Homosexual Equality. When one of their local groups was refused permission to have a disco he joined in their protests, and his name appeared in the local press. His ‘coming out’ was a surprise to his parents, but fortunately they were understanding and supportive.

Terry had the determination to stick up for his beliefs, which was just as well because even after decriminalisation life for homosexuals wasn’t much easier. He set up a mail order book business to provide information and support for the gay community, which he operated from his bedroom.

He was an avid reader and a keen, prolific writer. He started submitting articles to the nascent gay press in the late 1970s, contributing everything from book reviews to humorous pieces, from political comment to self-help advice. In 1983 he wrote a column for Gay Times highlighting continuing injustices and slurs against gays in the popular press. The editor liked it and Terry’s Mediawatch column promptly became a monthly feature, for there was no shortage of material. To carry out his assignment thoroughly he read every newspaper.

The tabloids were particularly antagonistic towards gays and he described their coverage of gay people, fuelled by the appearance of AIDS, as a ‘blood sport’. The Sun’s headline ‘Gays Axe Christmas’ is a relatively printable example, nearer the ridiculous end of the spectrum than the vitriolic.

Progress was glacial at first, but gradually his complaints to the press watchdogs and regulators began to take effect. Attitudes changed and one conspicuous sign of progress was when he became an agony aunt for Woman’s Own.

Mediawatch ran for 25 years, but journalism didn’t pay terribly well and for much of his career Terry’s main occupation was in social work, especially helping adults with learning difficulties. For light relief he wrote humorous books, while enjoying music and films. An annual task he gladly undertook was to organise a compilation of that year’s outstanding film clips for a benefit show for the Cinema Museum.

Born in the same county as Delius, in time he shared the composer’s scepticism of organised religion. He became convinced that religious doctrine, with its implicit rejection of homosexuality, was an impediment to its acceptance. He joined the National Secular Society, the aim of which is to disempower the church and remove its influence on the state.

The NSS was founded in 1866 by Charles Bradlaugh, who in the 1880s was elected as an MP for Northampton, only to be debarred from speaking because of his refusal to swear the Oath of Allegiance to Parliament on the Bible; as a non-believer, he wanted to affirm. Attempts to speak in the House of Commons, two Select Committee investigations, sundry debates, fines, and a brief imprisonment resulted in him forfeiting his seat – repeatedly. Voters returned him at four by-elections to make him a thorn in the side of the establishment. He finally took his seat in 1886 and two years later his Oaths Act was passed, making affirmation a legal right.

The NSS was at the forefront of the campaign that led to the 2008 abolition of ancient law of blasphemy. This was thirty years after it was last used in a prosecution by Mary Whitehouse against the proprietors of Gay News for publishing an obscene poem about Jesus.

Terry’s partner Keith Wood was already a senior figure in the organisation. Terry himself was President from 2006-17, and in that period he announced:

‘I would like us to position ourselves as a purely secularist organisation with a focused objective, that will not only champion human rights above religious demands but will also accept that religion has a place in society for those who want it, but on terms of equality, not privilege.’

Terry was popular, well-liked, and had a wide circle of friends. And he was humble; he never sought out praise or recognition.

It was only natural that Terry would attend and review the 1996 performance of A Mass of Life at St Paul’s Cathedral. His article appeared in The Freethinker, a pro-atheist magazine founded in 1881 with close connections to the NSS. A picture of Delius shared the front cover with that of another well-known atheist, with one headline above it proclaiming, ‘Unbelief spans art and science’ and one between them ‘From Delius to Dawkins’. It was reproduced in Journal 119 that year. [DSJ 119, pp40-2]

Terry wrote a full and thoroughly entertaining report for the Journal of the 2004 Delius Association of Florida’s Festival at Jacksonville. [DSJ 136, pp.85-89]. He clearly enjoyed the variety of events and traditional southern hospitality, but could not resist remarking on the anomalous ‘rather ostentatious prayer’ that preceded the Festival Dinner. Following that visit Terry kept up a long email correspondence with his Society friends in America.

Terry contracted bladder cancer in 2017. To begin with, treatment was successful, but it was only a temporary reprieve. He stood down from the National Secular Society in 2020 and later, when he knew the cancer was terminal, he wound down his affairs and said his goodbyes while he still could. He also updated his well-received autobiography The Reluctant Gay Activist.

On a pilgrimage to Limpsfield about twenty years ago Terry and Keith were paying their respects at Delius’s grave when they heard a cuckoo call out in full voice – the first they had heard that year. Fittingly, Terry’s ashes were interred next to Charles Bradlaugh’s grave in Brookwood Cemetery, Surrey. Some Delius was played during the ceremony.

Bill Thompson said of him:

‘Over the years, Terry Sanderson was a key player in the (now defunct) Yahoo Delius Group, sharing his thoughts on Delius concerts that he attended in the UK, as well as sharing published reviews from UK newspapers and magazines, which he continued to do in the Facebook Delius Discussion Group. Terry’s posts were always a real treat for us, especially those of us in the USA. I was pleased to meet Terry and Keith at the 2004 Jacksonville Delius Festival, where we had some time to visit about Delius’s music, and to attend the Jacksonville Symphony Orchestra concert conducted by David Lloyd-Jones. During the Festival we also enjoyed visiting further at a get-together at the home of Jeff Driggers and Bill Early, and later we all made the trek to visit Solano Grove. I wish that those annual Festivals could have continued, but sadly, it was not to be. I am thankful that I was able to stay in touch with Terry over the years via the internet. He will be missed. My sincere condolences to Keith and to Terry’s other family and friends.’

Jeff Gowers wrote of Terry:

‘I am so saddened to hear of Terry’s passing, even though I knew his health had declined. I had the pleasure (and it was a great pleasure) of meeting Terry and Keith at the Florida Delius Festival as well as at the Carnegie Hall production of A Mass Of Life as well as the meeting with other Delians for dinner beforehand. It was a genuine honour to have been given the chance to know this fine person. I’ll never forget how we both looked at each other after the performance of A Mass Of Life and we both had tears of joy in our eyes, for we’d just heard our favourite piece of music in the world. I will always think of Terry every time I listen to A Mass Of Life.

And Sir Ian McKellen paid this tribute just before Terry died on 12th June 2022.

‘25 years ago when I was discovering the delights of coming out, Terry’s journalism and books were an eye-opener – always rational and indignant, effortlessly on the high moral ground. I hope he is proud of his influence on the legal and social changes which his reporting encouraged.’

Jim Beavis (Editor)

The principal sources for this article are: https://www.secularism.org.uk/opinion/2022/06/obituary-former-nss-president-terry-sanderson

https://www.secularism.org.uk/news/2022/06/nss-mourns-the-loss-of-terry-sanderson https://www.buzzfeed.com/patrickstrudwick/this-man-spent-25-years-fighting-newspapers-over-their

Keith Wood, Terry’s partner for 40 years, writes:

‘Terry’s love of Delius was from an early age. He was a relentless visitor to the record collection in Rotherham Library where he methodically explored the music of less popular composers and soon alighted on Delius. I have always assumed that this affinity was reinforced by them both hailing from Yorkshire and being convinced atheists.

When Terry made new friends, a sign that they had been admitted into his inner circle was for them to be invited to watch Ken Russell’s film Song of Summer about Delius and Eric Fenby. When it was being screened Terry tried, invariably unsuccessfully, to hide the tears streaming down his face. He took particular delight in the scenes where Delius was dismissive of religion. The line ‘Parry would have set the whole Bible to music had he lived long enough’ always raised a chortle, as did the scene where Eric Fenby caught a priest in flagranti delicto with a young woman between pews. I was told, however, that Eric Fenby dismissed this as a fantasy invented by Russell. The film relates that Delius insisted that if Eric really had to go to church, he must do so only at the church in an adjacent village, rather than the one that was practically next door.

A few of our trips doubled as pilgrimages. That was certainly how Terry regarded the trip to Jacksonville Florida for its Delius Festival in 2004. The boat trip to Solano Grove with David Lloyd-Jones was a highlight. We tracked down the Delius family’s elegant house in Bradford, now paradoxically an Islamic centre. Every few years we visited the house Delius shared with his partner Jelka in Grez-sur-Loing near Fontainebleau, south of Paris. No trip there was complete without the mandatory excursion to the beautiful Grez, well worth the long trek from Bourron-Marlotte station and back. And what a treat it was to be shown around it, as we were on an organised tour.

Terry never missed any opportunity to attend a Delius concert, and took a party to a memorable performance of Koanga in Wexford’s (Ireland) magnificent Opera House during the 2015 Wexford Festival.

Terry took a group of friends to a performance of A Mass of Life at Gloucester Cathedral in 2001 as part of the public music festival for which admission was charged. The chaplain introduced the music, apparently without realising Delius was an atheist, ending with an ‘Amen’ – dutifully repeated by the audience – at which Terry audibly groaned. He complained in the name of the National Secular Society of which he was to become president

‘It seems to us an abuse of the captive, fee-paying audience to more or less oblige them to pray, or embarrass them by forcing them to refuse to do so.’

This was somewhat lampooned by the Telegraph, a little unfairly:

The NSS is in twisted knicker mode after some of its members witnessed people praying in a cathedral.’

Terry’s reverence for Delius was reflected in the full size bust of Delius’s head that was the focal point of our sitting room – almost like a religious icon. Shortly before Terry died, he gave the bust to an old friend, a fellow Delius admirer, in whose home it continues to enjoy pride of place.

Keith Wood

Other Tributes

BBC Radio Sheffield

In sound BBC Radio Sheffield – Paulette Edwards, Paying tribute to LGBTQ+ campaigner Terry Sanderson

The British Library, ‘Breaking the News’ 2022

The British Library exhibition “Breaking the News” chronicled the last 250 years of how news had been portrayed. It ran from 22 April – 21 August 2022. See Breaking the News – The British Library (bl.uk)

Very few exhibits featured an individual, but one such was devoted to Terry Sanderson and his Mediawatch columns in Gay Times. Above is the information plaque and one of the examples of his work as it appeared in Gay Times.